The sudden death of over 200,000 saiga antelopes in Kazakhstan in May 2015, more than 80% of the affected population and more than 60% of the global population of this species, baffled the world. The reason for mass death of saigas in Kazakhstan were found in the research of scientists of ‘Royal Veterinery College’. To explain the reasons of the death we are publishing the research paper.

In just three weeks, entire herds of tens of thousands of healthy animals, died of haemorrhagic septicaemia across a landscape equivalent to the area of the British Isles in the Betpak-Dala region of Kazakhstan. These deaths were caused by Pasteurella multocida bacteria.

But this pathogen most probably was living harmlessly in the saigas’ tonsils up to this point, so what caused this sudden dramatic Mass Mortality Event (MME)?

Saiga antelope

New research by an interdisciplinary, international research team has shown that many separate (and independently harmless) factors contributed to this extraordinary phenomenon. In particular, climatic factors such as increased humidity and raised air temperatures in the days before the deaths apparently triggered opportunistic bacterial invasion of the blood stream, causing septicaemia (blood poisoning).

By studying previous die-offs in saiga antelope populations, the researchers were able to uncover patterns and show that the probability of sudden die-offs increases when the weather is humid and warm, as was the case in 2015.

The research also shows that these very large mass mortalities, which have been observed in saiga antelopes before (including in 2015 and twice during the 1980s), are unprecedented in other large mammal species and tend to occur during calving. This species invests a lot in reproduction, so that it can persist in such an extreme continental environment where temperatures plummet to below -40 celsius in winter or rise to above 40 celsius in summer, with food scarce and wolves prowling. In fact, it bears the largest calves of any ungulate species; this allows the calves to develop quickly and follow their mothers on their migrations, but also means that females are physiologically stressed during calving.

With this strategy, high levels of mortality are to be expected, but the species’ recent history suggests that die-offs are occurring more frequently, potentially making the species more vulnerable to extinction. This includes, most recently, losses of 60% of the unique, endemic Mongolian saiga sub-species in 2017 from a virus infection spilling over from livestock. High levels of poaching since the 1990s have also been a major factor in depleting the species, while increasing levels of infrastructure development (from railways, roads and fences) threaten to fragment their habitat and interfere with their migrations. With all these threats, it is possible that another mass die-off from disease could reduce numbers to a level where recovery is no longer possible. This needs to be countered by an integrated approach to tackling the threats facing the species, which is ongoing under the Convention on Migratory Species’ action plan for the species.

"Atomic" exam for officials of Kazakhstan

"Atomic" exam for officials of Kazakhstan

EU Strategic Compass. The EU's Strategic Compass, PESCO & CARD

EU Strategic Compass. The EU's Strategic Compass, PESCO & CARD

Attack on Ganja: The Azerbaijani Embassy in Kazakhstan issued a statement

Attack on Ganja: The Azerbaijani Embassy in Kazakhstan issued a statement

A 19-year-old student from Kazakhstan has been arrested in Hong Kong

A 19-year-old student from Kazakhstan has been arrested in Hong Kong

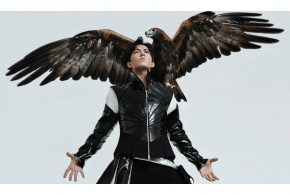

Dimash to perform in New York and Prague

Dimash to perform in New York and Prague

K. Tokayev sends condolences to President of Pakistan Arif Alvi

K. Tokayev sends condolences to President of Pakistan Arif Alvi